We have glorified working hard while demonising living well.

A world where people fight against dignity for others just to protect the illusion that their own pain had meaning

We’ve built a culture where exhaustion is a badge of honour, but joy must be earned, painfully, visibly, and preferably through burnout. We don’t just value contribution; we worship suffering as proof of legitimacy. And in doing so, we’ve made rest suspicious, ease shameful, and happiness something to apologise for.

The result? A world where people fight against dignity for others just to protect the illusion that their own pain had meaning. It’s not virtue. It’s trauma, dressed as ethics.

Burnout, in this twisted ethic, isn’t seen as a warning sign; it’s seen as a rite of passage. And if you flinch, if you pause, if you say, “I can’t do this anymore,” you’re branded soft. Fragile. A “sissy.” We’ve created a culture where collapse is courage, but rest is weakness. Where people are proud of how little they sleep, how many hours they grind, how much they endure, even if it’s killing them, literally.

And then we wonder why people snap. Why societies grow bitter. Why even modest proposals for collective wellbeing (like UBI) are met with rage. It’s because we’ve told people their only value is in their struggle. So if you take the struggle away, what’s left? They don’t just fear change. They fear losing their identity.

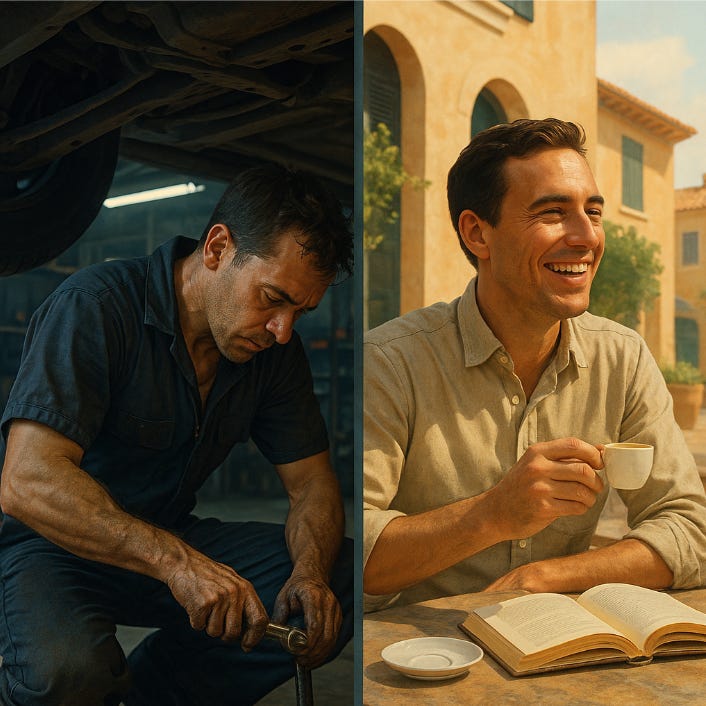

At a friend’s mechanic shop, I overheard a conversation which, in a nutshell, went like this: “Here I am working hard while others are enjoying themselves sitting at the café, doing nothing and getting paid for it (UBI).” It wasn’t that the people complaining were doing badly. Their resentment wasn’t economic, it was psychological. They were working hard for their money, and resented the idea that someone else could live comfortably without the same sacrifice.

This is the heart of it: the tension isn’t about income. It’s about perceived fairness. The mechanic didn’t resent being comfortable, he resented the idea that someone else could be comfortable without suffering as he did. It’s the trauma of struggle, mistaken for virtue. And in societies where hardship is internalised as moral currency, this dynamic plays out again and again, with people voting against their own interests just to ensure others don’t “get away with ease.”

This is the paradox of resentment-based politics and policy: people would often rather suffer together than watch someone else benefit unjustly, even if that benefit is dignity. And instead of asking, “Why am I struggling so much when others live well?” they ask, “Why should others live well without struggling like me?”

Many technocrats, economists, and even well-meaning progressives miss this: Wellbeing policies are not just economic policies; they are emotional and cultural battlegrounds. UBI, welfare, or any form of public dignity guarantee will always be attacked, not just by elites or conservatives, but by working people whose identity is forged in toil, unless the narrative is rewritten.

The tragedy? The system teaches them to direct their anger sideways, not upwards. The real enemy, the one extracting value from both the mechanic and the man at the café, walks free. Until we break that spell, until we stop glorifying exhaustion and shaming joy, even the best ideas for a better world will be voted down… by the very people they’re meant to help.

From day one, we are trained to moralise work. Not just to value it economically, but to see it as a measure of our worth. “Hard work builds character.” “Idle hands are the devil’s workshop.” “No pain, no gain.” These aren’t just sayings; they’re cultural programming. And that programming sets a trap. Because if work equals virtue, then not working equals sin. If you suffer, you’re noble. If you rest, you’re suspect. If you struggle, you’re admirable. If you’re at ease, you must be cheating the system.

This moral framing ensures that inequality becomes self-sustaining. Even when we have enough to provide for all, many will resist, not because it’s unaffordable, but because it offends their sense of earned value. So when someone receives comfort without sacrifice, when they skip the suffering we were told was required, it breaks the contract. Not the legal contract, but the emotional one. Not a system of shared abundance, but of earned suffering.

Anecdotally, 20 years ago, I was on a high, enjoying work so much that I casually said at a café, “Work for me is like a holiday.” And my good friend, trying to save face for me in front of a mutual colleague, quickly interjected, “Of course Aldo works very hard.” That one sentence, meant to protect, carried decades of hidden shame. As if I had revealed something indecent, that I loved what I did, and that it didn’t hurt. Because we’ve been trained to downplay joy, to apologise for ease, to earn the right to be happy only after visible sacrifice.

And here’s the darkest part: those at the top don’t believe any of this. They don’t think suffering is virtuous. They think winning is. They enjoy their yachts, their tax breaks, and their unearned income, without guilt. But the mechanic? The nurse? The teacher? They’re told their sweat is sacred.

This isn’t just inequality. It’s manufactured consent for inequality, through the myth of moral labour.

People are conditioned to declare virtue publicly, kindness, peace, compassion, while defending a system that punishes those very things in practice. It’s a survival strategy in a world where appearances matter more than alignment. Where, how you’re seen trumps how you live.

And in places where tax evasion is common, where the state is viewed as corrupt or incompetent, as in my mechanic-friend example, the social contract is already broken. So when a policy like UBI or basic welfare is introduced, it isn’t seen as a moral victory; it’s seen as another scam. Another undeserved handout in a world where people already feel cheated, not by the rich, but by their neighbours.

So they sabotage the very thing they claim to want: dignity, peace, well-being. Not because they don’t want those things, but because they don’t trust the structure they’re offered through. And worse, they don’t want others to have it if they feel they’ve suffered more.

It’s a dog chasing its tail. But the leash was put there by systems that reward struggle and punish ease, even when ease was the whole point of progress. And so, “Love thy neighbour” becomes: “as long as he doesn’t sit at the café while I’m changing oil.”